Peralta, Elena. (2016) La actualidad de la tipografía multiescritura. Màster Universitari de Tipografia Avançada, EINA, Centre Universitari de Disseny i Art de Barcelona (UAB) Barcelona.

Peralta, Elena. (2016) Relevance of multi-script typography. Master of Advanced Typography EINA, Centre Universitari de Disseny i Art de Barcelona (UAB) Barcelona.

Design Level

This Master Thesis focuses on design theory, being the research itself the main objective of the project. It has a high level of design not only because of its topic but also because of its methodology and presentation.

Innovation

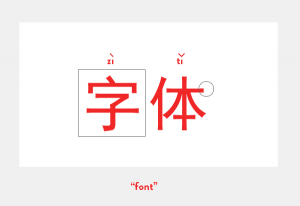

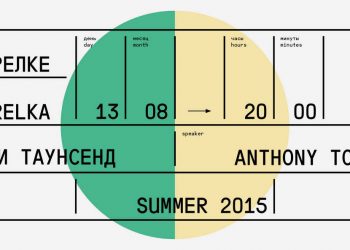

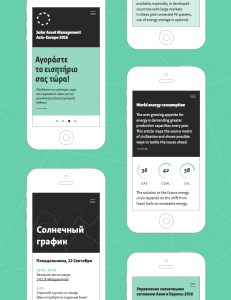

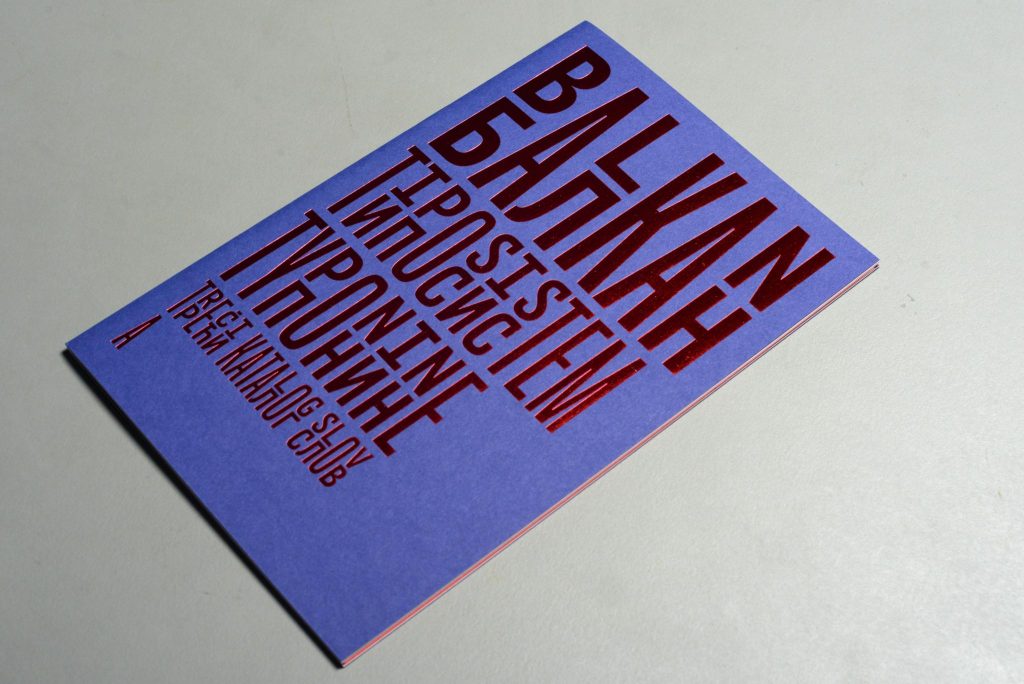

The aim project is the consideration of the present status of multi-script typography, a new field from typography design which intends to create tools for the use and representation of different languages on today’s written communication.

Although it is not highly innovative -because it is as a consideration of a pre-existing design topic- the Thesis’ specificity makes it quite distinctive. It is also interesting to point out that his kind of typographic practice stills pretty young, being first used on the late 90’s. Therefore, there are not many research projects focused on this topic.

Self-sufficiency

The Thesis talks by itself. It includes an exhaustive research, based on the knowledge of other experts of its area, combined with its own voice. It could be even published as a book by itself.

Outline and structure

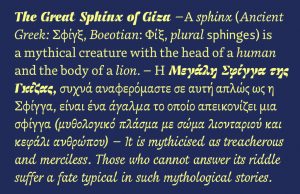

It has well defined objectives and methodology. At first it presents the context and basics of this kind of typographic practice and also clarifies common misunderstandings related to the topic.

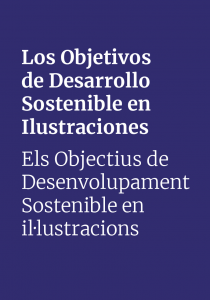

Afterwards it defines the connection between language, writing and multilingual communication with the use of typography.

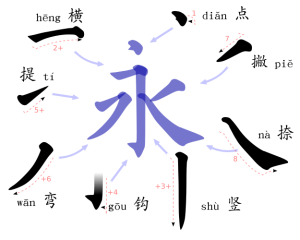

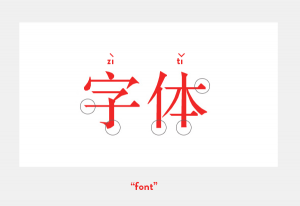

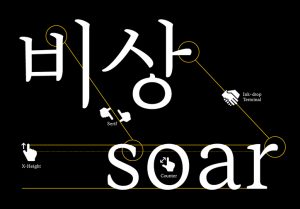

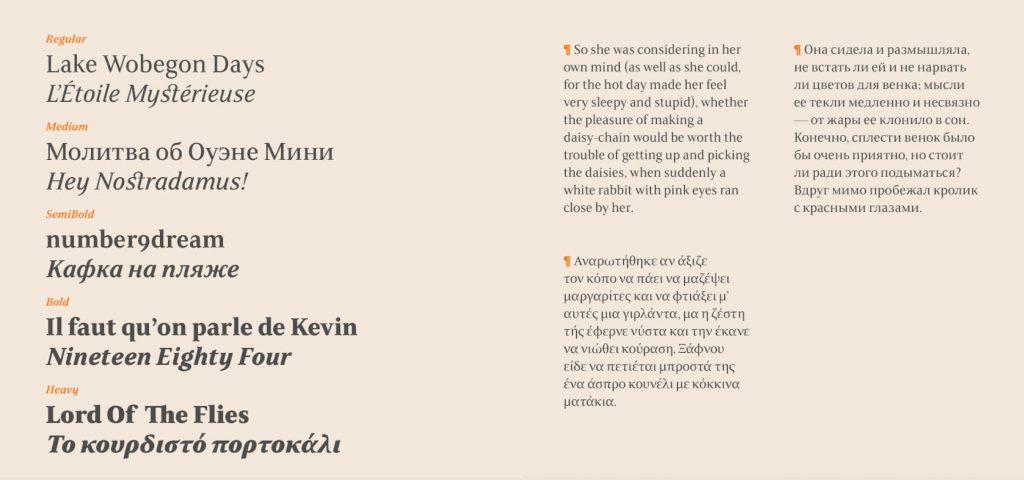

After the mention of the importance and purpose of the development of this kind of practice, it describes in detail the technical aspects of typography design and its correlation with language.

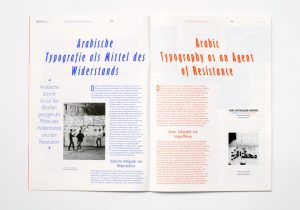

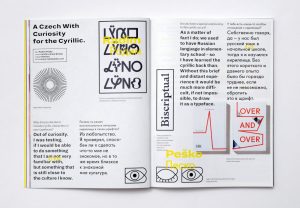

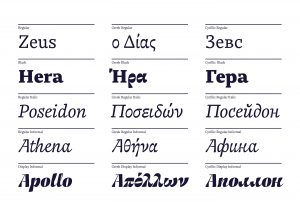

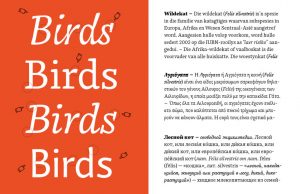

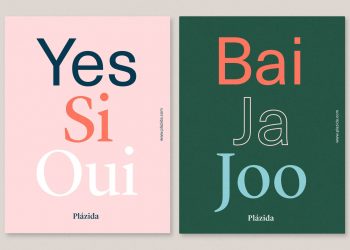

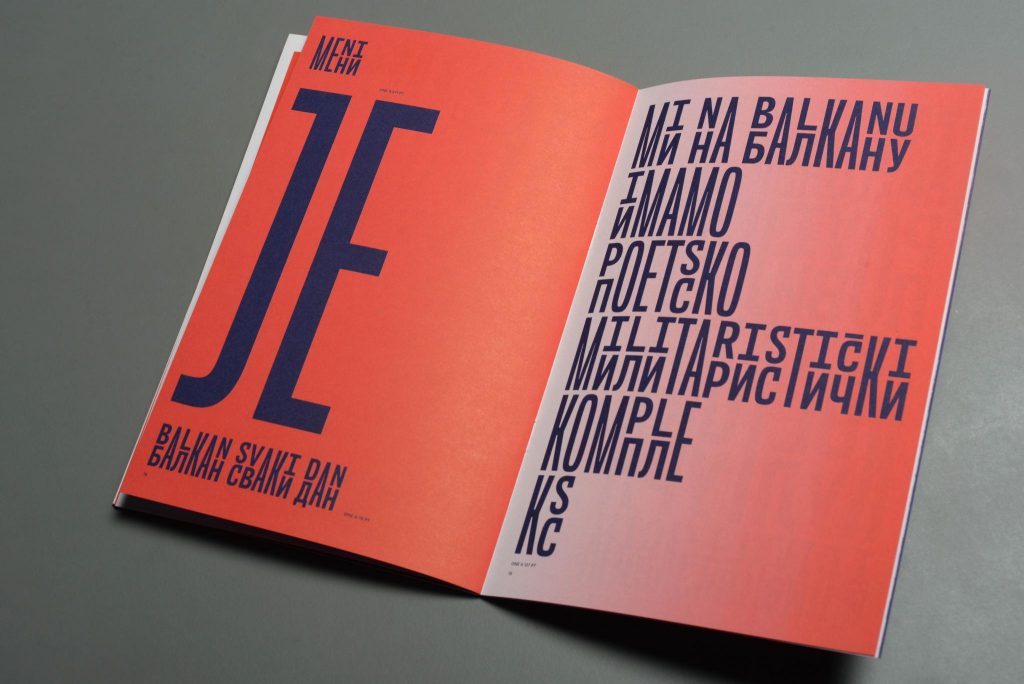

Then it focuses on multi-script typography, first examining its short history and big names with a following description of all the technical and esthetical specifications characteristic of these fonts.

Next it compares particular cases of other languages like Arab or Latin, using all the parameters described in the previous chapters. Finally, it comes to an end with the conclusion and personal considerations.

Communication

Proper language characteristic of the design theory. It defines complicated terms and also uses technical vocabulary specific from its field. It is pleasant to read and very coherent.

Scale of work

The thesis far-reaching and presents a broad research with the examination of specific cases, which need their own context and study. It is a great amount of work, even lacking of a practical part. However, it would be interesting to see the translation of the theoretical part into the design practice.

Orthography and accuracy

Really accurate writing, stylistic coherent and heterogeneous.

Bibliography

The project is based on a vast bibliography, characteristic of a theoretical master thesis. It includes materials found on books, magazines, websites and online publication. The themes are diverse including design, typography, philology, sociology and communication.

The sources are meticulously quoted and separated properly by different classes.