GAMIFICATION OF ELECTIONS – PART 6

In this article I will dissect the popular language learning app “Duolingo”. I will take a look at the different gamification elements in play, the UI design and UX of the app and analyse them. Disclaimer: I won’t go into the monetization efforts of this app – as this would be enough to justify a blog article on its own.

Duolingo uses implicit game mechanics: it is a learning app that uses game mechanics, instead of being a game with learning elements attached to it. This means that we will see the full potential of gamification methods in “serious apps”. After taking a first look at the player journey, we see that the different phases don’t really differ too much from another. The Onboarding phase is essentially the same as the Endgame phase. This is nothing too uncommon in implicit apps like this, since the main goal and the main obstacles don’t change much through the journey. Languages don’t get harder the more you learn.

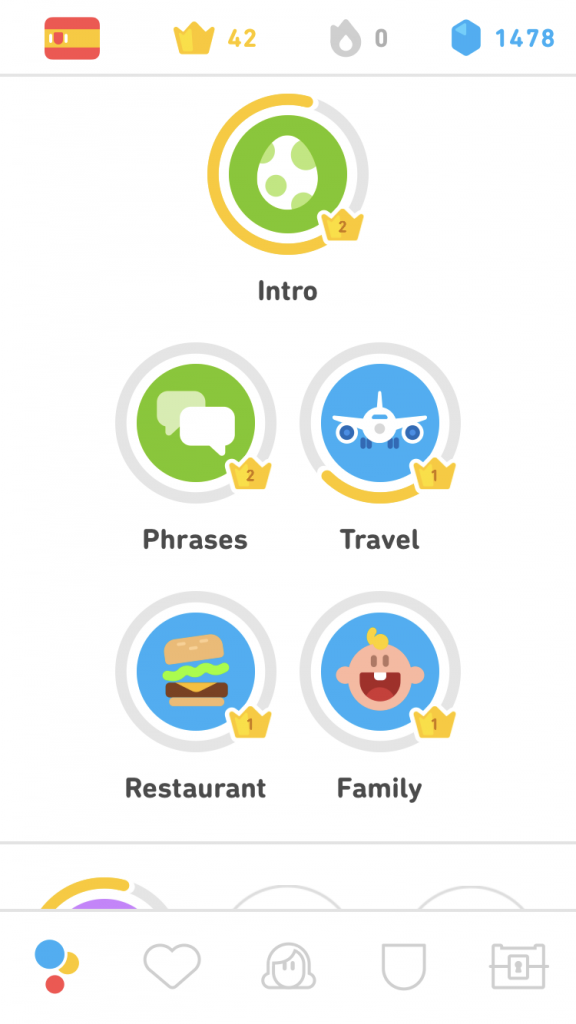

The learning process starts easily enough: The first lesson is unlocked to start off. After that, further lessons unlock – sometimes only one, sometimes two or more at the same time, to give the student some agency in what words to tackle next. This whole progress is still a mostly linear – and rather narrow – path (comparably to a skill tree in classic games). There are checkpoints at regular intervals where learners take progress tests to recap the previous group of lessons. Even without some clunky progress bar this feels like an accomplishment – like a Miniboss fight in a video game.

The lessons themselves are multi-levelled. Taking a lesson several times (with varying exercises) will slowly increase the lessons level progress. So, while the student actually only needs to reach level one of the lesson to unlock the next lessons, they can keep taking the same lessons to further increase their proficiency. Here we discover one of the weaker gamification aspects – the learner has little motivation to repeat the lessons after mastering the first level. There is little discernible gain in continuing old lessons, when the student can take on the brand new lessons they just unlocked (CD#7 Curiosity).

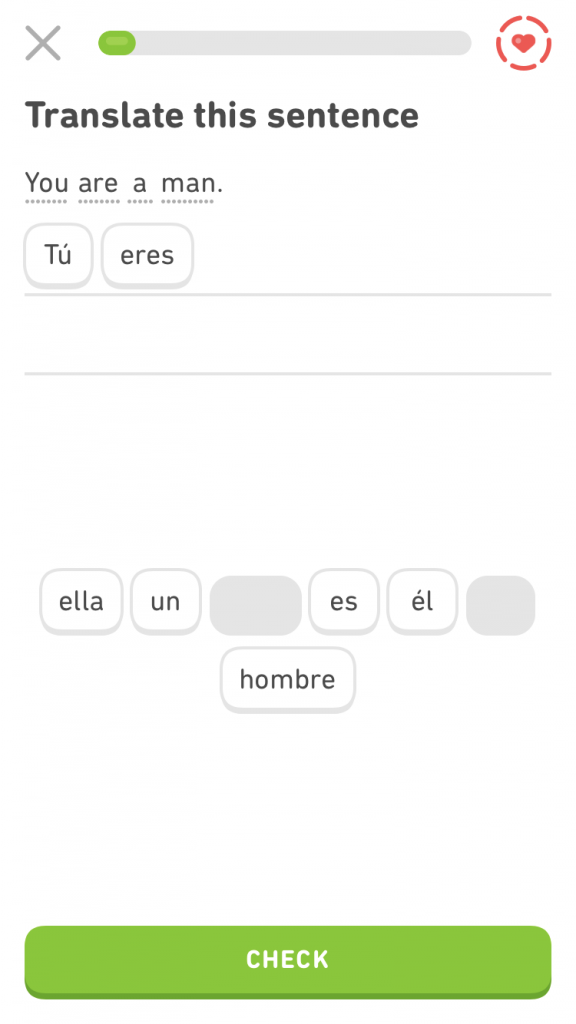

The lessons themselves are straightforward. Listening, writing and sometimes some multiple choice or mix-n-match games. Heavy focus in the early stages lies on simplicity in the controls. No actual typing is required, but rather just selecting pre-written text blocks to put together a whole sentence. Here shines Duolingo: This mechanic lets the student focus on actually learning the language, instead of distracting them with typos, or the occasional fight with autocorrect. Every now and then a little animation of “Duo”, the service’s adorable owl mascot, interrupts the lesson to congratulate you on “getting 5 correct answers in a row” and other little achievements. A lot of those mechanics focus on Core Drive #2 Development & Accomplishment.

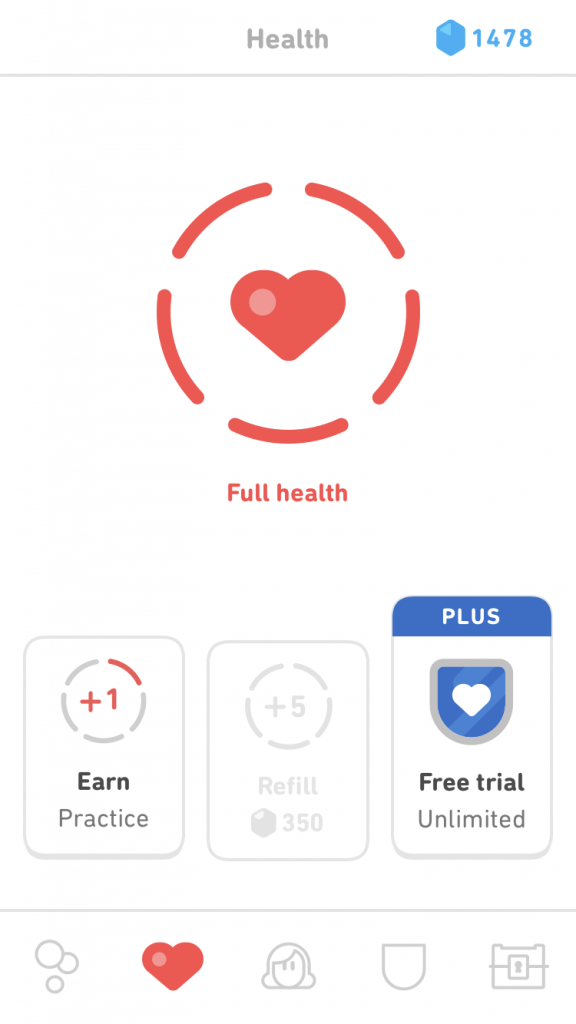

When the player makes a mistake, they lose a fifth of their “health”. When they run out of “health” they are barred from taking another lesson. The health will slowly regenerate one piece at a time, with the app notifying the player when they’re back at full strength. These health mechanics play heavily into core drive #6 and #8, Scarcity & Impatience and Loss & Avoidance respectively. The student wants to do good in order to avoid the loss of all of their “tries” and making them wait for a set amount of time before trying again increases anticipation for the next lesson.

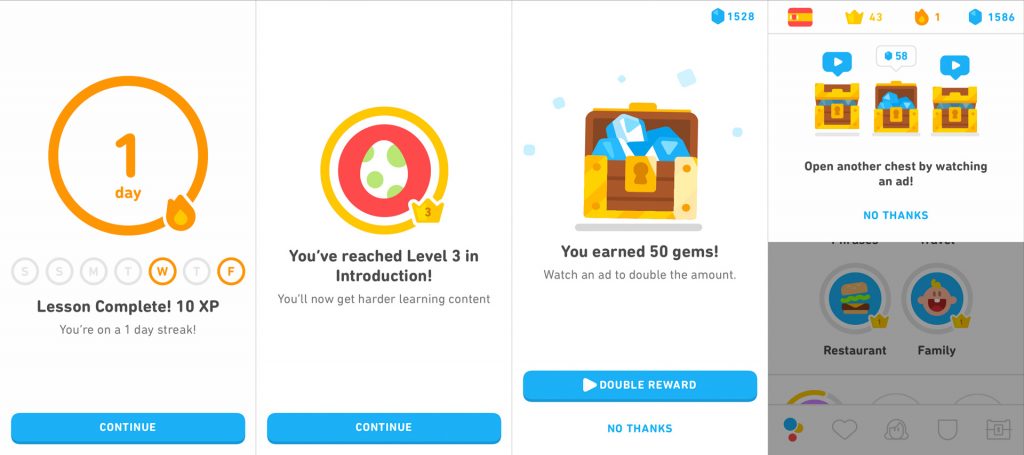

After each lesson the “rewards” will be handed out. First, the player is shown the progress screen. Their daily goal progress meter fills up – when reaching the daily goal (set by the players themselves in a clever effort to add endowment* to the goal, making it their goal, thus increasing the incentive to actually accomplish it) a little flame lights up, indicating that their hot streak is on. Small icons below show the previous 7 days and on which of these days the learner did or did not accomplished their daily goals. The lesson progress meter also fills up, adding to the student’s sense of development (CD#2) and letting them know when they unlocked a new, harder level of the lesson. And then the reward arrives. Upon completing a lesson-level, a treasure chest pops up, gifting the player 50 gems – Duolingo’s in-app currency. This is called a “Fixed Action Reward” or “Earned Lunch” by Yu-Kai Chou. The player gets 50 gems every time they finish a lesson-level, thus acting as an incentive. I will dive into greater detail on the purpose of these gems in a few paragraphs. When the daily goal is reached, the student will receive another reward – a loot box (Surprise Reward). Presented with three treasure chests with different amounts of gems inside, the learner chooses one (CD#7 Unpredictability & Curiosity). A short text beneath it urges them to come back the next day for more rewards (Impatience). Fixed Action rewards are not entirely unproblematic, as studies have shown that placing extrinsic motivation on activities we already like doing reduces our intrinsic motivation for doing them (see “How rewards backfire”, below).

Learning is always better in groups and Duolingo knows that. With a secondary but nevertheless heavy focus on Core Drive #5 (Social Influence & Relatedness) present in the app. Secondary because the social aspects are completely voluntary. Students can create “clubs” – groups, where they can learn together, get updates on their respective progress, help each other out, or even be mentored by a “club leader”. The learner will then get regular updates on the others’ progress (Social norm), motivating them further. Custom emojis and phrases let the group members cheer each other on and a leaderboard introduces a competitive element to the learning. Independently from groups, Duolingo lets the students show off their progress to the world via Facebook.

A few more classic gamification elements round out the whole experience. As mentioned, the student will regularly earn gems. These gems act as an in-app currency. Learners can spend gems in the in-app store to buy different upgrades or boosters. Boosters constitute small perks or advantages that help the player in their efforts – like an increased XP-gain, more health for more tries etc. Boosters are, per definition, timed advantages, only lasting for a certain amount of time, or are altogether just a one-off bonus (e.g. to refill the player’s health). Additionally, the Duolingo store also offers special courses – dating vocabulary or idioms and phrases for example – that can be bought with gems. This is a smart move, as it acts as a sort of secondary, intermediate goal for the learner (saving up/earning enough gems to buy these lessons) besides their long-term goal – mastering the language.

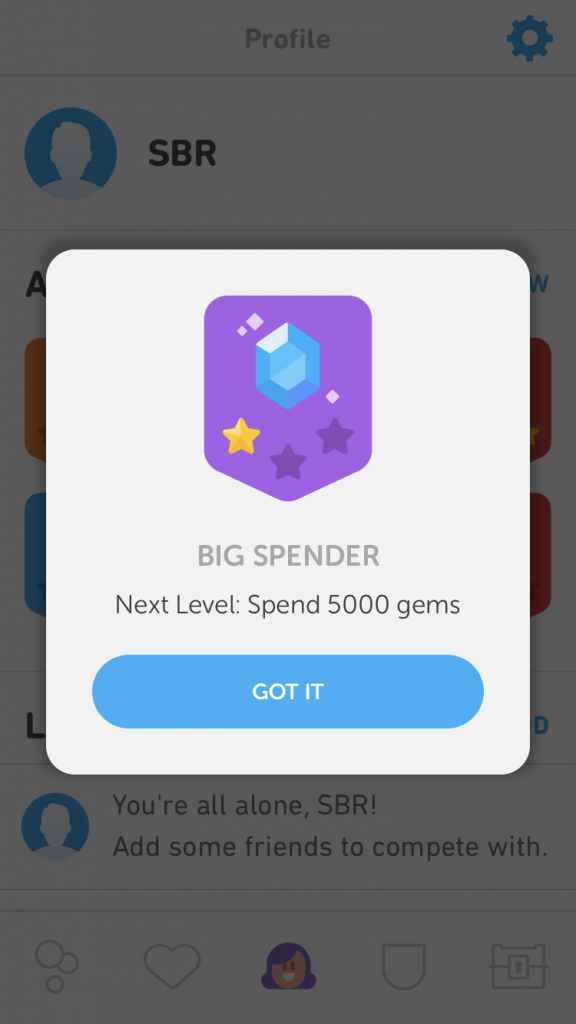

Last but not least among those classic elements, are the obligatory badges/achievements. These are certainly the least fleshed out gamification elements within Duolingo and seem more of a remnant of an early design for the app. In a multi-tiered approach, learners can earn badges/stars for special activities. Smartly designed achievements can lead the players to their next move – as a sort of a tutorial. Jane McGonigal writes in her book “Reality is Broken” about this topic:

Satisfying work always starts with two things: a clear goal and actionable next steps toward achieving that goal.

So, while good designed achievements can serve as a guide on how to use the app/game or get the most out of it, badly designed achievements should be avoided. Bad achievements are for example, challenges that seem arbitrary without any real connection to the game world (“Complete a lesson before 8am” or “Spend 5000 gems”). Condescending achievements should also be avoided – challenges that are set so low, that when players are awarded with them, they don’t feel accomplished, but rather patronized. They can be played for a laugh, as a joke, or to introduce the achievement-system as a whole, but should be carefully considered. In the Duolingo app, the badges themselves don’t really show up during use – even when they are being rewarded – and most students probably never encounter them at all. Therefore, they are, in their current implementation, rather useless as both intrinsic motivation and as a beginner’s tutorial.

In conclusion it can be said, that Duolingo did an admirable job in designing their learning experience as well as using gamification techniques and gameplay mechanics quite well. Apart from the aforementioned achievements, the mechanics support the learner’s goal very well and aren’t just there for optics, but they all serve an appropriate purpose.

The final chapter will circle back to the beginning of this series and ask the question: How can we use all of those features and techniques to improve elections?

Up next: Cast vote? Yes / No / Cancel

*See “endowment effect”: In psychology, this is the hypothesis that people ascribe more value to things merely because they own them.

Further reading:

Jane McGonigal, Reality is Broken:

https://tinyurl.com/googlebooks-realityisbroken

https://www.spring.org.uk/2009/10/how-rewards-can-backfire-and-reduce-motivation.php