Titel der Arbeit: Designing a Persuasive Game for Children’s Safety Awareness

Verfasser: Tuomas Alahäivälä

Ort & Datum: vorgelegt 2017 an der University of Tampere

Studienrichtung: Magisterstudium in „Internet and Game Studies“

Autor: Cornelia Neuwirt

Interactive Math Stories

Interactive Mathematical Stories (IMS) are interactive storybooks that provide children with the combination of an enjoyable story and a guidance on strategy and concepts to solve mathematical problems (Ginsburg, 2016). There seems to be great potential to learn more about the design, use and effect of IMS as existing research on the topic is limited (Ginsburg, 2018).

CURE Runners – Game Mechanics in Action

CURE Runners is an e-learning game developed by the Austrian developer agency OVOS. It aims to teach players about money management using the redeemable points of the game as a virtual economy. Which will already sound familiar to anyone who read the previous blogpost, discussing the most common game mechanics. In this post I want to have look at if and how CURE Runners, incorporated these mechanics:

Common Game Mechanics

There are seven basic game mechanics that should be considered when creating a gamified experience: points, levels, leaderboards, badges, onboarding, challenges/ quests, and engagement loops.

Points

In order to motivate the player to take certain actions in alignment with the behavioral objectives, each action should have a certain point value assigned to it. These points should be part of the experience point system which is important to rank and guide players through the game. Other point systems that can be included in a game are redeemable points, which are used to create a virtual economy and are used as „currency“ within the system, skill points which are assigned only to specific activities alongside the core storyline or objectives to develop an additional skillset. Moreover, there are karma points, whose only purpose is to spend them and reputation points which are the most complex point system as they are used to create credibility and trust.

6 Characteristics of Games

The instructional content of educational games should be packaged in these game characteristics as the input to the game cycle. The cycle itself consists of user judgment or reactions such as enjoyment or interest followed by user behavior for example time on task which then triggers further system feedback. This cycle should create self-motivated gameplay, repeating the instructional content and thus lead to the desired learning outcomes.

However, there are quite varied point of views as to which characteristics are essential to games. Garris, Ahlers and Driskell have identified the following six broad dimensions:

Designing Problems to Promote Higher-Order Thinking

For problem based learning (PBL) the required level of content knowledge should be made clear at the start or the players’ current level assessed and the game adjusted accordingly. If the problems are too difficult players will get frustrated. On the other hand, if the problems are not challenging enough they will neither engage players nor stimulate critical thinking. Therefor, problems should be just slightly above players’ current skill level so they need to extend their knowledge base and skills to solve.

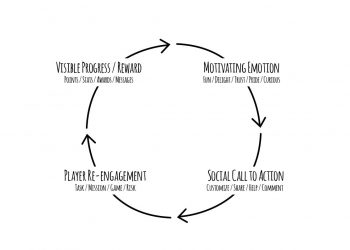

Game Design-Loop

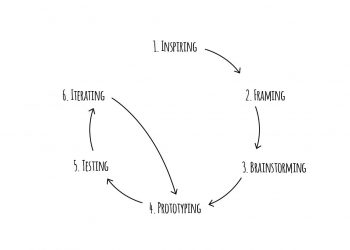

The core design loop for game design consists of six steps:

- Inspiring

Take a decision about what kind of experience the game should create for the players. In the case of educational games it is also important to decide what knowledge should be trained. - Framing

Assess the parameters of the game. Set reasonable but fierce deadlines in order to force yourself to work more efficiently and really get things done. - Brainstorming

Start putting the ideas down on paper. In this state there is no good or bad – just write everything down and sort out later. - Prototyping

Take the best ideas from the brainstorming, further develop them and create a prototype. - Testing

Test the prototype in order to see what works and what needs revision. - Iterating

Use the learnings from the testing to further improve the process.

Source:

- Gary, Justin; Think like a Game Designer – The Step-by-Step Guide to Unlocking Your Creative Potential, Aviva Publishing, 2018

Digital Math Games

(fig.: Grendel Games, „Garfield’s Count Me in“, 2016)

„Peter buys 10 eggs at the market, at home he makes scrambled eggs for him and simon with 2 eggs each – how many eggs are left afterwards?“ – we all remember the story problems from our school time. Story problems put the otherwise often rather abstract math problems into a (more or less) relatable context, making the matter more tangible. In these kind of problems students need to understand the question, decode the given information and find the right methods to come up with the answer. They are more engaging than a plain formula to solve and are urging students to think about the problem at hand in a much broader way, connecting information and training mathematical comprehension. (1)

Don’ts of Gamification

Sometimes a good way to figure out which way to go, is to start with deciding where not to go. There are lots of people out there who already had their fair share of experiences with creating serious games and share their learnings. So I compiled a list of common mistakes or don’ts described in various blogs.

Game Mechanics and Knowledge Encoding

An educational game does not need to have a serious storyline in order to transmit serious information or knowledge. Rather it is the fundamental mechanics of the game that are important. The mechanics determine how the player interacts with and consumes the presented information. Dr. Christopher See suggests in his TEDxTalk that a good way to create an educational game is to start with the content and concepts that should be covered in the game. Then build them into gamified training environment with mechanics hat help embed the information effectively in the memory. (1)